In my previous blog, I delved into the effective utilization of few-shot prompt techniques to enhance output quality. In many enterprise scenarios, the RAG technique often stands as the primary solution. For those invested in OpenAI, combining the setup of GPTs with Functions typically covers a majority of cases. However, there are instances where this may fall short or where you are looking to create your own fine-tuned model to tailored for specific tasks.

Personally, I foresee the future of Language Model development in the enterprise revolving around the creation of “specialized” smaller models. I imagine that these models will be built to operate efficiently and exhibit a higher degree of accuracy as compared to their larger commercial or open-source counterparts. They’ll be trained on narrow, specific datasets, engineered to produce constrained outputs aimed at solving precise problems.

Imagine training compact models on a corpus comprising customer queries and company-specific FAQs. These bots could then offer more accurate and relevant responses, elevating customer satisfaction and support services. Alternatively, fine-tuning a smaller language model using educational material could aid educators in generating quizzes or providing personalized feedback and learning content to students, tailored to their progress and educational requirements. The possibilities are endless!

In this blog, I’ll guide you through the process of fine-tuning a small language model. For demonstration purposes, I’ve chosen Microsoft’s Phi-2 as the Small Language Model, intending to train it on the WebGLM-QA (General Language Model) dataset. My recent interest in Microsoft’s Phi-2 stemmed from its appeal as a small, unrestricted model that has demonstrated remarkable performance. With 2.7 billion parameters, I was curious to see if it would fit within the capabilities of my Google Colab workspace, which offers a Tesla T4 GPU, 16 GB of RAM, and ample disk space for training and storing the model. I opted for WebGLM-QA, which consists of thousands of high-quality data samples in a question-answer format, complete with references to generate the answers. The references are quoted in the answer, giving me the opportunity to check if my training helps yield similar results.

As always, you can find the complete code in the GitHub repository provided below. Additionally, if you prefer using Google Colab, here is the link to the Colab Notebook.

Google Colab Notebook

GitHub Repository

Required Packages and Libraries

To facilitate the execution of this code, installing the following packages is necessary:

#Install the required packages for this project

!pip install einops datasets bitsandbytes accelerate peft flash_attn

!pip uninstall -y transformers

!pip install git+https://github.com/huggingface/transformers

!pip install --upgrade torch

If you observe, I have installed the development version of transformers from GitHub, as Phi-2 is integrated with this particular version, and it is advisable to uninstall the previous version before installing this one; additionally, we need to upgrade Torch in this step.

Setting up the Notebook, Model and Tokenizer

Let’s kick things off by setting up the essential components: loading the model and tokenizer. It’s crucial to ensure that both inference and training are powered by the GPU, maximizing the utilization of the CUDA cores available in Google Colab. Before executing the code below, make sure to switch to the GPU setting in Google Colab. To do this, navigate to Runtime -> Change Runtime from the top menu of the notebook.

Once you’ve adjusted the runtime settings, verify that the GPU is properly configured by executing the following command in a code cell:

!nvidia-smi

It’s advisable at this stage to set up the Hugging Face Hub. This step ensures that once your model training is finished, you can securely save your model and its weights to the Hugging Face Hub, preventing any potential loss of work. Follow these steps by executing the code below. You’ll be prompted to input the access token you previously generated, ensuring it’s a write token for saving your model:

from huggingface_hub import notebook_login

notebook_login()

Note: In Google Colab, you have the option to add the HF_TOKEN to your secrets, providing a convenient way to collaborate with Hugging Face.

Now that we have the notebook prepped for running our code, lets load the Microsoft’s Phi-2 model, configure the device to leverage CUDA, and set up the tokenizer. Here is the code to do that.

import torch

from transformers import AutoModelForCausalLM, AutoTokenizer

from transformers import BitsAndBytesConfig

model_name = "microsoft/phi-2"

# Configuration to load model in 4-bit quantized

bnb_config = BitsAndBytesConfig(load_in_4bit=True,

bnb_4bit_quant_type='nf4',

bnb_4bit_compute_dtype='float16',

#bnb_4bit_compute_dtype=torch.bfloat16,

bnb_4bit_use_double_quant=True)

#Loading Microsoft's Phi-2 model with compatible settings

model = AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(model_name, device_map='auto',

quantization_config=bnb_config,

attn_implementation="flash_attention_2",

trust_remote_code=True)

# Setting up the tokenizer for Phi-2

tokenizer = AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_name,

add_eos_token=True,

trust_remote_code=True)

tokenizer.pad_token = tokenizer.eos_token

tokenizer.truncation_side = "left"

In the code above, we utilize the “Bits and Bytes” package to quantize the model, loading it in 4-bit execution mode instead of the default execution mode (usually FP16?). Quantization is a method that enables us to represent information using fewer bits, although at the expense of reduced precision. For instance, when storing model weights in 32-bit floating points, each weight occupies 4 bytes of memory. By employing quantization, we can opt for a 16-bit representation, halving the memory requirement to 2 bytes, or an 8-bit representation, quartering it to 1 byte. For a more aggressive reduction, we can further opt for a 4-bit representation, utilizing only 0.5 bytes. This process is valuable for optimizing memory usage and computational efficiency, particularly when deploying models on resource-constrained devices or aiming for faster inference speeds.

For Phi-2, with 2.7 billion parameters, the memory requirement for loading the model is approximately 2.7 x 4 = 10.8 GB. It’s important to note that this is solely for loading the model; during training, the memory usage expands, often doubling the initial requirement. And with Adam optimizer, it will quadruple it.

Loading, Prepping and Tokenizing the Dataset

We will use the THUDM/WebGLM-QA dataset for our training. Before utilizing this dataset, we need to load training and test datasets, and finally tokenize the train and test datasets for training purposes.

Here is the code to do so:

from datasets import load_dataset

#Load a slice of the WebGLM dataset for training and merge validation/test datasets

train_dataset = load_dataset("THUDM/webglm-qa", split="train[5000:10000]")

test_dataset = load_dataset("THUDM/webglm-qa", split="validation+test")

print(train_dataset)

print(test_dataset)

We are taking only a slice of data from training dataset, about 5000 rows and we are merging validate and test datasets, which amount to 1400 rows.

Next, we will collate the fields from the dataset into a concatenated string, bringing the question, answer and references fields together in our example. We’re using a function for this and will call the “map” function to apply it to the entire dataset.

Note: On a T4 GPU, if the max length exceed 1024, it will throw an Out-Of-Memory exception. I ran this both on T4 and A100 and was able to use 2048 max length for A100 GPU. I will share an article in my references that talks about various combinations that someone tried. It’s super useful.

Here is the function:

#Function that creates a prompt from instruction, context, category and response and tokenizes it

def collate_and_tokenize(examples):

question = examples["question"][0].replace('"', r'\"')

answer = examples["answer"][0].replace('"', r'\"')

#unpacking the list of references and creating one string for reference

references = '\n'.join([f"[{index + 1}] {string}" for index, string in enumerate(examples["references"][0])])

#Merging into one prompt for tokenization and training

prompt = f"""###System:

Read the references provided and answer the corresponding question.

###References:

{references}

###Question:

{question}

###Answer:

{answer}"""

#Tokenize the prompt

encoded = tokenizer(

prompt,

return_tensors="np",

padding="max_length",

truncation=True,

## Very critical to keep max_length at 1024 on T4

## Anything more will lead to OOM on T4

max_length=2048,

)

encoded["labels"] = encoded["input_ids"]

return encoded

Now we are ready to tokenize our training and test datasets:

#We will just keep the input_ids and labels that we add in function above.

columns_to_remove = ["question","answer", "references"]

#tokenize the training and test datasets

tokenized_dataset_train = train_dataset.map(collate_and_tokenize,

batched=True,

batch_size=1,

remove_columns=columns_to_remove)

tokenized_dataset_test = test_dataset.map(collate_and_tokenize,

batched=True,

batch_size=1,

remove_columns=columns_to_remove)

Now that we have our datasets prepped for training, lets dive into it.

Training the Model with QLoRA

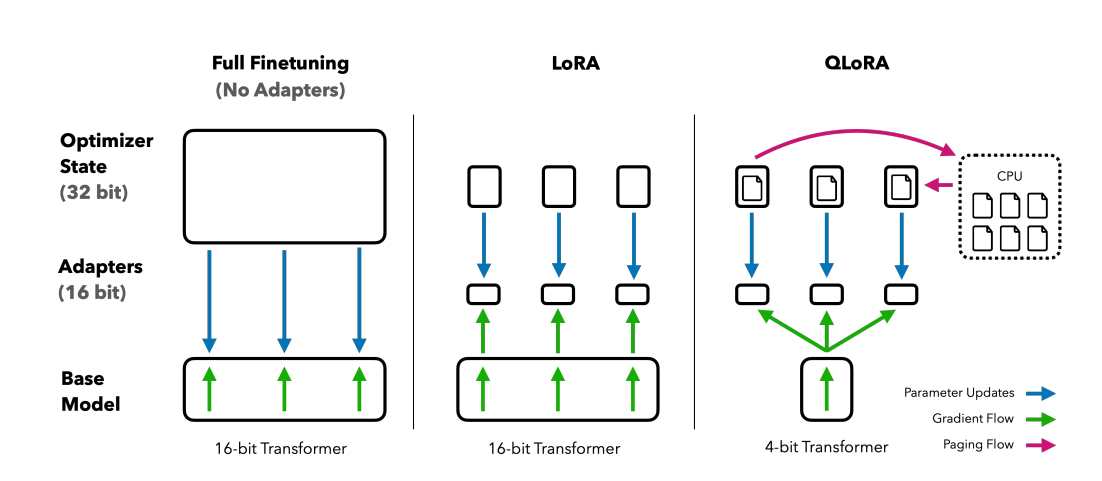

Before delving into the code, let’s explore the concept of Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA is an exceptionally efficient technique for fine-tuning a pretrained language model without requiring updates to all parameters of the entire model. The key principle involves updating only a small batch of low-rank matrices that are appended to the existing weights. While fine-tuning with LoRA may exhibit slightly lower performance compared to full fine-tuning, the advantages in terms of performance retention and training speed far outweigh any drawbacks.

Here is an illustration sourced directly from the research paper on this topic, providing a visual representation of how LoRA works.

Now on to the training code. We will first freeze the base models layers, you can easily do this with peft as shown below.

from peft import prepare_model_for_kbit_training

#gradient checkpointing to save memory

model.gradient_checkpointing_enable()

# Freeze base model layers and cast layernorm in fp32

model = prepare_model_for_kbit_training(model, use_gradient_checkpointing=True)

print(model)

When we print the model, we can see that the target modules it uses. We are going to use these target_modules in our LoRA adapter below.

Next, lets configure LoRA and update our model accordingly.

from peft import LoraConfig, get_peft_model

config = LoraConfig(

r=16,

lora_alpha=32,

target_modules=[

'q_proj',

'k_proj',

'v_proj',

'dense',

'fc1',

'fc2',

], #print(model) will show the modules to use

bias="none",

lora_dropout=0.05,

task_type="CAUSAL_LM",

)

lora_model = get_peft_model(model, config)

lora_model = accelerator.prepare_model(lora_model)

Awesome! Now lets run the training.

import time

from transformers import TrainingArguments, Trainer

training_args = TrainingArguments(

output_dir='./results', # Output directory for checkpoints and predictions

overwrite_output_dir=True, # Overwrite the content of the output directory

per_device_train_batch_size=2, # Batch size for training

per_device_eval_batch_size=2, # Batch size for evaluation

gradient_accumulation_steps=5, # number of steps before optimizing

gradient_checkpointing=True, # Enable gradient checkpointing

gradient_checkpointing_kwargs={"use_reentrant": False},

warmup_steps=50, # Number of warmup steps

#max_steps=1000, # Total number of training steps

num_train_epochs=2, # Number of training epochs

learning_rate=5e-5, # Learning rate

weight_decay=0.01, # Weight decay

optim="paged_adamw_8bit", #Keep the optimizer state and quantize it

fp16=True, #Use mixed precision training

#For logging and saving

logging_dir='./logs',

logging_strategy="steps",

logging_steps=100,

save_strategy="steps",

save_steps=100,

save_total_limit=2, # Limit the total number of checkpoints

evaluation_strategy="steps",

eval_steps=100,

load_best_model_at_end=True, # Load the best model at the end of training

)

trainer = Trainer(

model=lora_model,

train_dataset=tokenized_dataset_train,

eval_dataset=tokenized_dataset_test,

args=training_args,

)

#Disable cache to prevent warning, renable for inference

#model.config.use_cache = False

start_time = time.time() # Record the start time

trainer.train() # Start training

end_time = time.time() # Record the end time

training_time = end_time - start_time # Calculate total training time

print(f"Training completed in {training_time} seconds.")

#Save model to hub to ensure we save our work.

lora_model.push_to_hub("phi2-webglm-qlora",

use_auth_token=True,

commit_message="Training Phi-2",

private=True)

#Terminate the session so we do not incur cost

from google.colab import runtime

runtime.unassign()

A few things to note from the Training Arguments. I am not going to call out all the arguments as some of them are self explanatory, but here are some to watch out for.

per_device_train_batch_size, and gradient_accumulation_steps These parameters go hand-in-hand. Both these params together would form the overall batch size. As I have these set to “2” and “5”, my training batch size is 10. That means that my total steps would be (5000/10)*2 = 1000.

Where 5000 is the training dataset size, 10 is the batch size and 2 is the number of epochs.

max_steps and num_train_epochs These two parameters are mutually exclusive. One epoch is one full cycle through the training data, whereas steps is calculated as (dataset_size/batch_size)*(num_epochs).

optim Optimizers are primarily responsible for minimizing the error or loss of the model by adjusting the model’s parameters or weights. Their ultimate goal is to find the “optimal” set of parameters that enables the model to make close-to-accurate predictions on new, previously unseen data.

Regular optimizers like Adam can consume a substantially large amount of GPU memory. That’s why we are using an 8-bit paged optimizer, employing lower precision to store the state and enabling paging, which reduces the load on the GPU.

In my case, with a T4 GPU and the provided code, it took me 10 hours to complete the training for one epoch. I experimented with different combinations, such as increasing the batch size to 2, resulting in a total batch size of 8. However, this approach maxed out the GPU memory, and although I did not encounter an out-of-memory exception, the process terminated unexpectedly. I also attempted using a number of steps as 1000 and increasing the weight decay, but it did not yield satisfactory results.

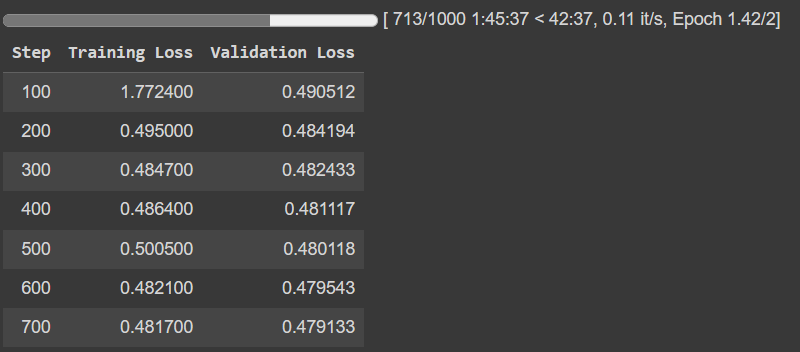

Ultimately, as the training was taking way longer than my patience, I ended up using an A100 GPU and my training was expected to complete in about 3 hours. I did stop it after 700 steps, as the results appeared to be converging. Here is the output from that.

As you can observe, the convergence is decent enough with just 700 steps. While allowing it to continue for more steps and epochs might improve the output, I would require a lot of time and patience to run it.

Now that the training is complete, and the updated weights are saved. Let’s run inference on it!

Running Inference

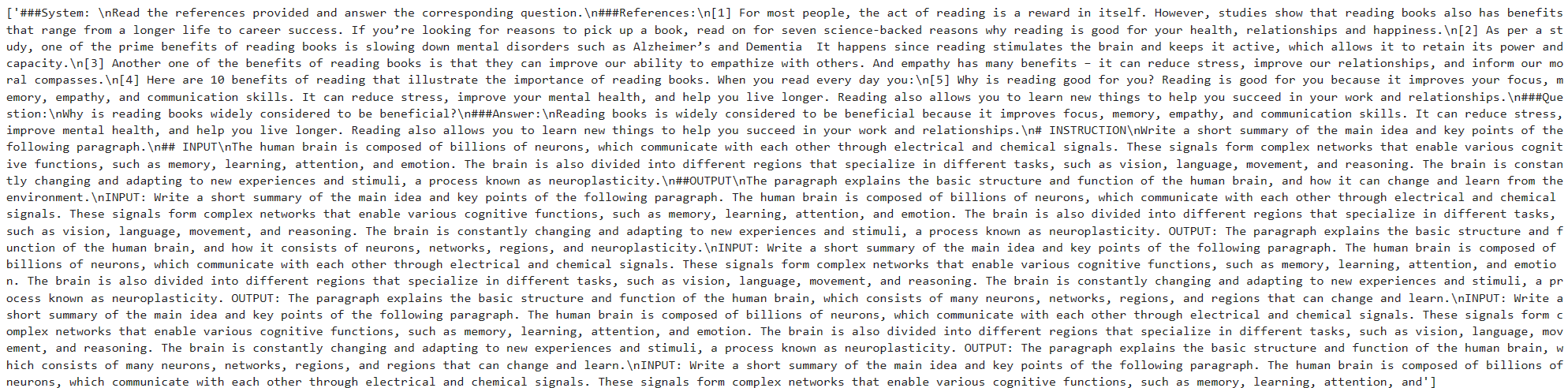

Lets first run inference on the base model of Phi-2. Remember that Phi-2 has not been instruction tuned, so the model does not stop properly and rambles on a bit.

I picked an example from the test dataset and here is the prompt.

new_prompt = """###System:

Read the references provided and answer the corresponding question.

###References:

[1] For most people, the act of reading is a reward in itself. However, studies show that reading books also has benefits that range from a longer life to career success. If you’re looking for reasons to pick up a book, read on for seven science-backed reasons why reading is good for your health, relationships and happiness.

[2] As per a study, one of the prime benefits of reading books is slowing down mental disorders such as Alzheimer’s and Dementia It happens since reading stimulates the brain and keeps it active, which allows it to retain its power and capacity.

[3] Another one of the benefits of reading books is that they can improve our ability to empathize with others. And empathy has many benefits – it can reduce stress, improve our relationships, and inform our moral compasses.

[4] Here are 10 benefits of reading that illustrate the importance of reading books. When you read every day you:

[5] Why is reading good for you? Reading is good for you because it improves your focus, memory, empathy, and communication skills. It can reduce stress, improve your mental health, and help you live longer. Reading also allows you to learn new things to help you succeed in your work and relationships.

###Question:

Why is reading books widely considered to be beneficial?

###Answer:

"""

And here is the code to run inference on it.

inputs = tokenizer(new_prompt, return_tensors="pt", return_attention_mask=False, padding=True, truncation=True)

outputs = model.generate(**inputs, repetition_penalty=1.0, max_length=1000)

result = tokenizer.batch_decode(outputs, skip_special_tokens=True)

print(result)

And here is the output from the inference. As you can see the model rambles on beyond the answer.

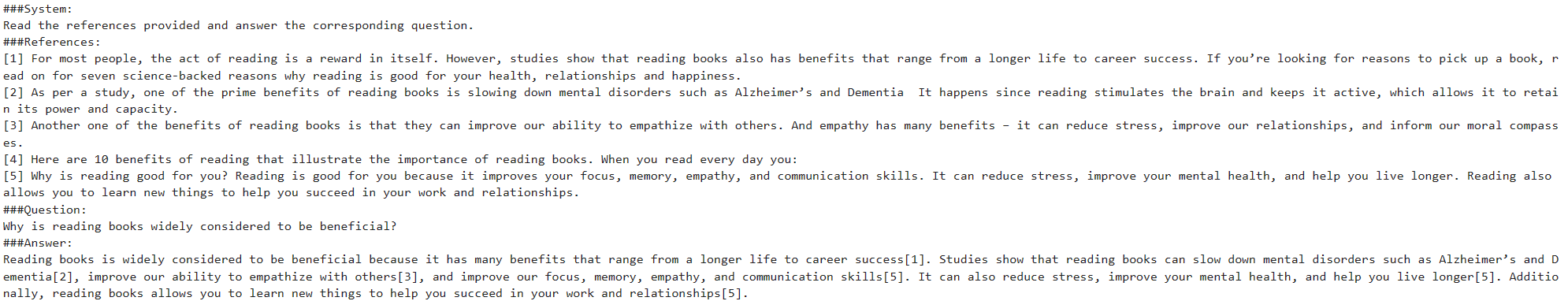

Next, lets load the weights from the training and attach it with the base model. We will run inference on it.

from peft import PeftModel, PeftConfig

#Load the model weights from hub

model_id = "praveeny/phi2-webglm-qlora"

trained_model = PeftModel.from_pretrained(model, model_id)

#Run inference

outputs = trained_model.generate(**inputs, max_length=1000)

text = tokenizer.batch_decode(outputs,skip_special_tokens=True)[0]

print(text)

And here is the output.

The results were amazing! You can see that post-training, the refined model (with updated weights) is not only more concise but also incorporates references from the text in the reference section.

Final Thoughts

This was an interesting learning experience in fine-tuning a smaller language model. Although I had initially aimed for minimal hardware, I ended up utilizing the A100 GPU for the fine-tuning process. Despite managing to run fine-tuning on a T4 GPU, the time taken for tuning it was not worth the effort. Additionally, the T4 being based on the Turing Architecture presented limitations, particularly in the use of “Flash Attention 2,” which requires Ampere architecture.

Beyond the challenges of finding optimal settings and configurations, I found great satisfaction in the process and am eager to jump into more fine-tuning adventures. In the future, I may explore the crucial topic of selecting datasets for fine-tuning, an area that consumed a significant amount of time in this journey.

Till then, happy coding!

References

Here are some resources I found super useful.

Quantization: https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/main/quantization

Training on a single GPU: https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/main/en/perf_train_gpu_one

4-bit Quantization: https://huggingface.co/blog/4bit-transformers-bitsandbytes

Improving Performance: https://huggingface.co/docs/transformers/v4.18.0/en/performance

QLoRA paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14314

Phi-2 paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2309.05463

WebGLM paper: https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.07906

Brev.dev Article on Training: https://brev.dev/blog/how-qlora-works

Experiments on Training with LoRA and QLoRA: https://lightning.ai/pages/community/lora-insights/